Adult Learning_Med Culture's contextually rooted and multi-faceted approach

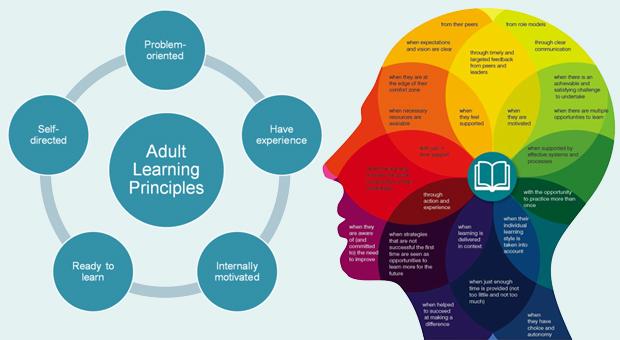

The principles of andragogy (how adults learn), as articulated by Knowles (1984), suggest that adults learn best when they are involved in diagnosing, planning, implementing and evaluating their own learning. In other words, adult learners:

- Need to know why they need to learn something before undertaking to learn it

- Need to be responsible for their own decisions and to be treated as capable of self-direction

- Have a variety of life experiences which represent the richest resource for learning

- Are ready to learn those things they need to know in order to cope effectively with real life situations

- Are motivated to learn when they perceive that it will help them perform tasks they confront in those life situations.

In adult learning, the role of the trainer is less about conveying knowledge and information (teacher centred) and more about creating and maintaining a supportive climate that promotes the conditions necessary for learning to take place (learner centred): so with an increased emphasis on process rather than content. In such settings, experiential learning methods e.g. case studies, role play, participant presentations and group tasks such as problem-solving are regarded as particularly useful (see Train the Trainers’ Toolkit, NHS Education for Scotland).

According to Kolb (1984), the process of adult learning follows a pattern or cycle comprising four stages: experiencing, reflecting, conceptualising and planning next steps. The idea is that while adults are more likely to remember things if they involve real experience, experience on its own won’t get us very far. We also need to reflect on our experiences, make ‘generalisations’ (conceptualise) about them and then plan how we’d do things next time. It’s called a learning cycle because it is possible to start at any point and repeat the process many times; but the order in which we go tends to be the same. Using an example of baking bread, we might start with a recipe (conceptualisation), make the bread (experience), think about why it didn’t rise (reflection), decide we need to leave it somewhere warmer (conceptualisation), make adjustments to the recipe (planning) and try again (experience).

Honey and Mumford (1986a, 1986b) took Kolb’s thinking further and concluded that adults tend to develop learning styles or preferences derived from the four stages of the learning cycle. Thus, activist learners tend to immerse themselves fully in experiences, enjoying the moment and thriving on new challenges; reflectors tend to listen and analyse before contributing, needing time to think things through before acting; theorists like principles, models, systems and theories on which to base their experiences; pragmatists like trying out ideas, theories and techniques to see if they are likely to work in practice, or be applicable in real life. The idea here is that learning experiences must cater for all these preferences to be fully effective.

It would be fair to say that these theories of learning – like others – have been the subject of critical examination and that (adult) learning is a continually evolving field of enquiry.

Consequently, while Med Culture took note of this thinking, it did so in a way that informed rather than circumscribed, and allowed its own emergent, contextually rooted and multi-faceted approach to come into being.